She’s 13 feet of granite curves and unapologetic cleavage – and soon she’ll be gone.

Denmark’s Big Mermaid statue, unveiled in 2006 as a bold, modern counterpoint to Copenhagen’s iconic Little Mermaid, created by Edvard Eriksen, is set to be removed from public view after years under the cloud of public disapproval.

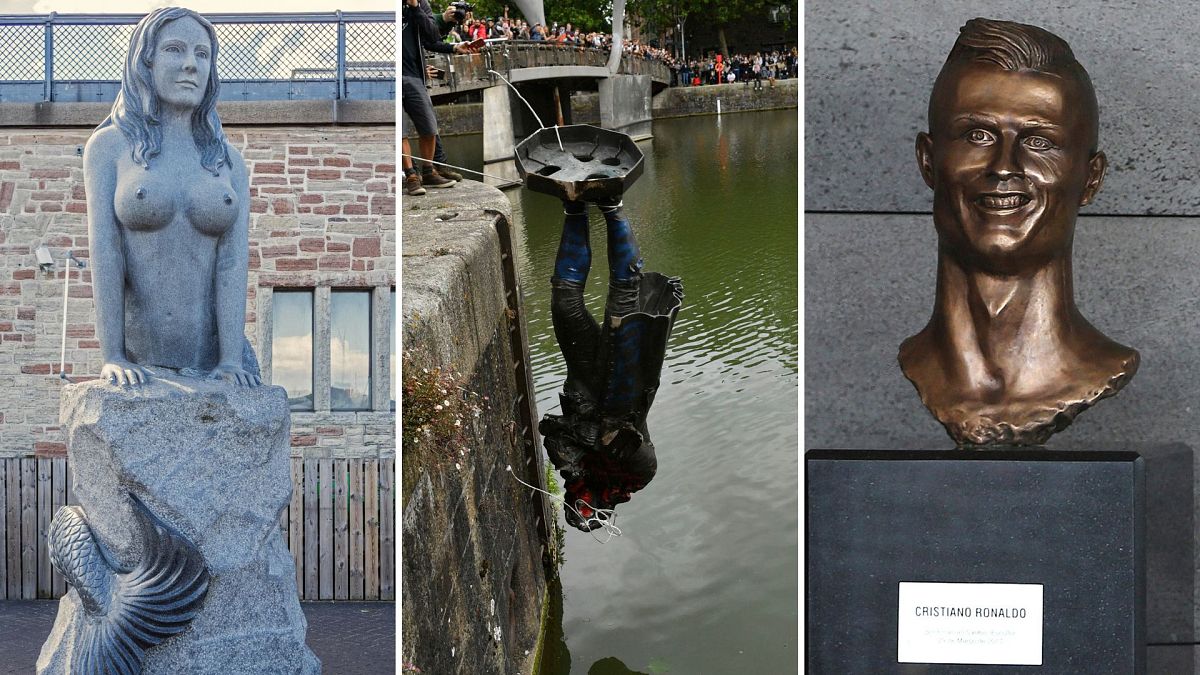

Critics have long described her as “ugly and pornographic” and her exaggerated form has been accused of cheapening rather than celebrating female beauty.

In 2018 she was quietly relocated from Copenhagen’s waterfront to Dragør Fort, several miles south, in what looked suspiciously like exile.

Now, Denmark’s agency for palaces and culture says she will be removed altogether, concluding that she does not fit with the cultural heritage of the century-old fort.

She’s far from alone. Across the world, statues once celebrated have faced the chopping block, judged too ugly, too offensive, or too politically toxic to stay on their plinths.

Take the statue of 17th century slave trade Edward Colston in Bristol – a man responsible for overseeing the transportation of an estimated 84,000 Africans into slavery. In 2020, his bronze likeness met a dramatic and widely-publicised fate: furious protesters pulled it from its plinth during Black Lives Matter demonstrations and rolled it through the streets, before dumping it into the harbour, poetically where ships of the slave trade had once docked.

The act sparked a national reckoning over who deserves a place in Britain’s public memory, and what role statues play in that story.

London’s Docklands soon followed by removing a statue of Robert Milligan, another slave trader, within days.

Today, Colston’s statue rests in a museum, serving as a reminder of the histories we inherit and the ones we choose to confront.

Beyond Britain, Antwerp took down a statue of King Leopold II in 2020, long vilified for brutal atrocities in the Congo. The following year, Spain dismantled the last public statue of fascist dictator Francisco Franco under its Historical Memory Law. And across the Atlantic, Confederate generals have been falling for years, from Robert E. Lee in Richmond to P.G.T. Beauregard in New Orleans.

In Poland, it was scandal, not history, that toppled Roman Catholic priest Father Henryk Jankowski’s statue in Gdansk after allegations of sexual abuse towards a minor. Protesters tied ropes around it and brought it down themselves. Another accused priest, Eugeniusz Makulski, had his memorial removed and altered by the church.

But not all removals are weighty historical, scandalous reckonings. Sometimes, they’re just… extreme cases of being, to put it nicely, aesthetically challenged.

In Madeira, Portugal, a very questionable bronze bust of newly-engaged Cristiano Ronaldo drew ridicule for its unflattering likeness of footballing legend Cristiano Ronaldo. Unsurprisingly, within a year it had been replaced by a more photogenic version.

Then there are statues that vanish under more mischievous, mysterious circumstances…

Earlier this year, a bronze statue of US first lady Melania Trump, unveiled in her Slovenian hometown of Sevnica in 2020, was sawn off at the ankles and taken in the night. Most recently, a protest sculpture of banker David de Pury – flipped upside down to highlight his ties to the slave trade – was stolen from a city square in Switzerland.

And it’s not just human figures at risk… Two drunken men in England were sentenced to community service and fined after they ripped in half and stole a Paddington Bear statue earlier this year.

The fate of these statues – whether toppled in protest, quietly relocated, or stolen in the dead of night – reveals that public monuments are far from permanent. They reflect society’s values and priorities, and force us to ask: Which stories do we want to honour, and which are we ready to question?

And maybe, just maybe, let’s leave Paddington out of it.