With the cultivation of genetically modified plants banned in nearly all EU countries, the European Commission wants to treat products of the latest lab techniques as equivalent to conventional crops. Governments appear to be getting on board.

The EU has moved a step closer to lifting the stringent regulation of a new generation of genetically modified crops created using new genomic techniques (NGT), with a clear majority of governments signalling support for a Polish compromise proposal.

The European Commission wants to create a new category of genetically modified crops created using modern gene editing techniques that would be subject to light-touch regulation, and treated as largely equivalent to conventional strains. Currently all GMOs are subject to strict safety testing and traceability requirements.

Poland, chairing intergovernmental talks during its six-month EU Council presidency, held an informal vote on Friday (21 February) among national delegates in its third bid to broker a deal by tweaking provisions on the thorny issue of the patentability of new-generation GM crops.

A handful of countries, mainly in the southeast of the EU, have consistently opposed the GMO liberalisation proposal. But the latest meeting appears to have tipped the balance in favour of creating the new category of gene-edited crops that would be exempt from the bulk of current regulations.

Belgium, previously hamstrung by its fractious federal structure, has chosen to back the proposal under a newly installed right-wing government. “We still have an issue with the patents but in a spirit of compromise, we decided to constructively support [the proposal],” a Belgian diplomatic source told Euronews.

With the European Parliament having already agreed to back the core elements of the deregulation proposal – albeit while opposing patents on NGT crops – environmental groups are now concerned that liberalisation is looking increasingly likely.

Friends of the Earth Europe urged agriculture ministers to reject the deregulation proposal, with food campaigner Mute Schimpf saying the EU executive was “putting corporate interests ahead of nature and citizens’ best interests”.

“Deregulating new GMOs won’t benefit Europe – farmers, consumers, and the environment will pay the price just to please Bayer and its merry corporate friends,” Schimpf said, naming the German agro-chemical giant that merged with its US peer Monsanto in 2018.

Qualified majority

Berlin – two days before a general election, but with a long history of vacillating over key agro-tech issues – abstained, along with Bulgaria. But even without the EU’s largest member state, there appears to be sufficient support to move forward.

Another diplomatic source told Euronews that only Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia confirmed their continued opposition to the proposal, with Greece likely to join them pending government confirmation. The seven fall well short of a blocking minority.

All other member state delegates supported the Polish compromise, although four – Italy among them – signalled they required the final nod from their governments.

A Polish diplomat said the latest text had met with a “good reaction” from governments, paving the way for a vote among national permanent representatives in Brussels next month. Agriculture ministers could then formally adopt their joint position on the proposal at one of two scheduled meetings, in late April or late May.

After that the Council would enter back room talks with the European Parliament to hammer the legislation into its final form, a process that typically takes several months – but the fundamental deregulatory aim appears now to be backed by both legislative bodies.

‘No scientific rationale’

Environmental campaigners argue that patentable plants would lead to monopolistic practices by a small number of giant corporations, to the detriment of farmers. But they also vehemently oppose the NGT proposal on safety grounds.

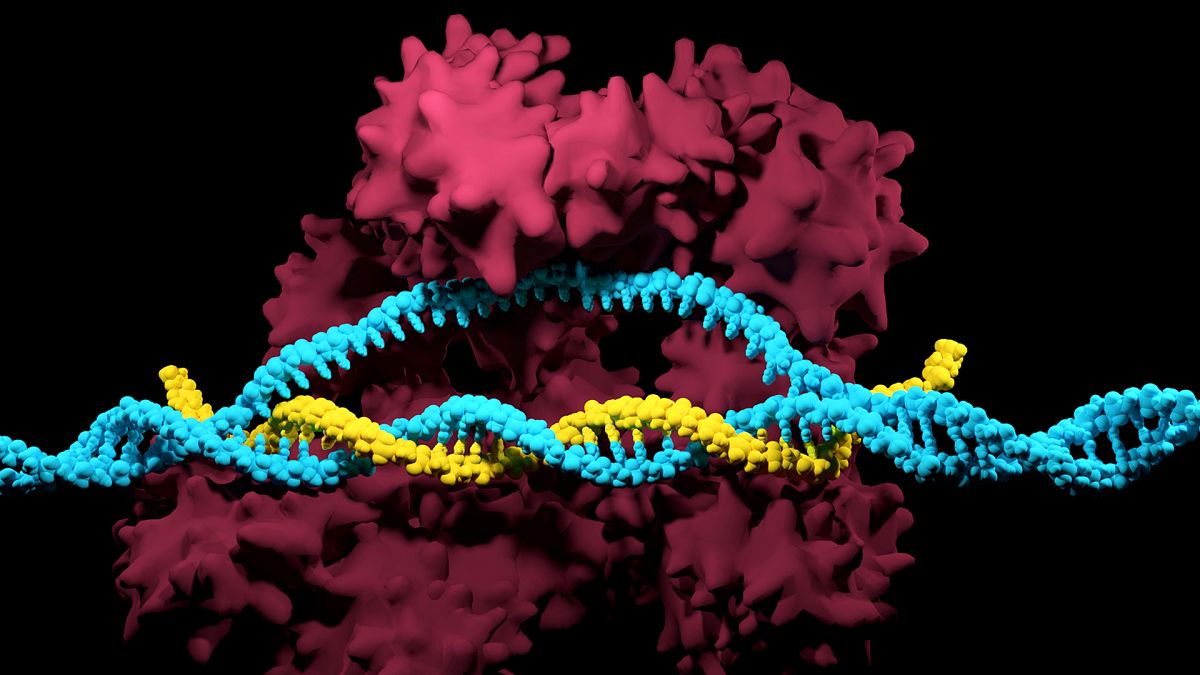

For a genetically engineered plant to be considered equivalent to a conventionally bred strain, it must contain no more that 20 point changes to its DNA – the famous ‘double helix’ containing the genetic code of life.

“However, there is no scientific rationale behind such a ‘magic threshold’, given there is no correlation between the number of mutations and the level of risk,” some 30 groups including Friends of the Earth Europe and GM Watch wrote to health commissioner Olivér Varhélyi last week.

The proposed criteria “completely ignore the fact that even small changes to the genetic material can lead to life forms with new characteristics that differ significantly from those resulting from conventional breeding or those found in natural populations”, they wrote just a week after a similar warning from some 200 small farmers groups and NGOs.

While first-generation GMOs involved transplanting a gene from one organism into another, new genomic techniques – including CRISPR/Cas9 ‘genetic scissors’, which won its inventors the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 – allow scientists to make precision edits to the genomes of plants or animals.

The new technology allows scientists to rewrite genetic code at will, rather than simply shifting genes from one cell to another, and researchers are already exploring the potential for using generative AI to programme new properties into organisms – a prospect that has been met with both excitement and deep concern.

Transgenic crops will remain subject to the existing GMO Directive, with stringent safety and traceability rules and an opt-out that has allowed all but a handful of EU governments to ban cultivation on their territories. Spain remains for now the only country in the union with significant production of GM crops.