As the Tate Britain exhibition of this year’s Turner Prize nominees goes on show, Euronews Culture speaks to curator Linsey Young and reviews the 2024 cohort.

Britain’s clashes with individual cultural heritage is the predominant theme of this year’s Turner Prize nominees, as an exhibition of the four nominees for this year’s prize opens to the public today at London’s Tate Britain.

Pio Abad, Claudette Johnson, Jasleen Kaur and Delaine Le Bas presented a combination of the works they were nominated for alongside older pieces for the public to experience, ahead of the judges making their decision on the winner at a ceremony in the gallery on 3 December.

“This is a very strong year,” Linsey Young, a curator at Tate Britain tells Euronews Culture. As you go through the exhibition, each section represents distinct mediums, styles, and cultures. From Kaur’s now-iconic Ford Escort covered in a doily to Abad’s intricate drawings; this is one of the most diverse stylistic offerings in recent memory.

While the nominees are the culmination of the jury’s discussions on who represents the best developments in contemporary art, the exhibition opening is the first time all four artists’ work is seen together, and creates a new impression of the year’s candidates, Young explains.

“What’s happened this year is that all four artists are exploring the most pertinent issues that we’re talking about today in the arts,” Young continues. Decolonialisation, anti-imperial struggles, borders, migration and the role of the museum in the world are the major themes. “What I love is that they’re thinking about that on a broad level, but also at a family level.”

Britain, its role in the world and influence on other cultures, is the most dominant theme in the show.

Pio Abad, the Filipino artist who was nominated for his solo exhibition ‘To Those Sitting in Darkness’ at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, brings work from across his career in a striking display of his exploration of colonial legacies and everyday life.

Dominating his space, Abad drawing of the underside of Powhatan’s Mantle, a deer hide at the Ashmolean Museum that was “given” to King James I by the Native American Powhatan Paramount chiefdom. Abad calls it an “atlas for the many lands that can never be recovered.”

Alongside his ink and screen print drawings, it’s the intricacy of Abad’s work that shines here. His multi-media work brings items back from the jaws of history and reanimates them with tender consideration.

It’s a far more meditative section than the following area by Jasleen Kaur. There, the doily-decked Ford Escort booms pop songs, as you walk under a netting containing assorted remnants of the Glaswegian artist’s Sufi-Indian heritage. Included in the suspended ceiling is everything from ceremonial thread bracelets to bottles of half-drunk Irn Bru, creating a collage of life as a Muslim in Scotland.

Most affecting is a recording of Kaur singing Sufi Islamic devotional music alongside worship bells as part of her work opposing colonialism.

“Keeping these skills and that heritage alive is a tool against oppression,” Young says.

Although enjoyable, the Kaur’s section feels like the least engaging, with the individual items lacking a cohesive theme or narrative beyond their singular connection to Kaur’s background.

Delaine Le Bas recreates her nominated show ‘Incipit Vita Nova. Here Begins The New Life/A New Life Is Beginning’ that was hosted at Secession in Vienna last year. The Roma artist takes audiences through a three-section installation experience of paintings, sculptures, architecture, writing, performance, sound, light, and textile.

Death, loss, and renewal are the themes of the three rooms, explicated by the horror-movie set overtones of the first room. Slashes of paint on scratched tapestry hang down as ominous music focuses your attention.

The following room, a mirrored chamber beams a film of what seems like the hazy memory of an interaction with a folkloric character, before finally, the audience is taken to the least oppressive of Le Bas’s rooms, where there are still startling images of disembodied legs with blood dripping alongside. Where Le Bas’s work stumbles is bringing the audience into the myriad cultural references to the artist’s Roma heritage, despite the strong impression it nevertheless makes on the audience.

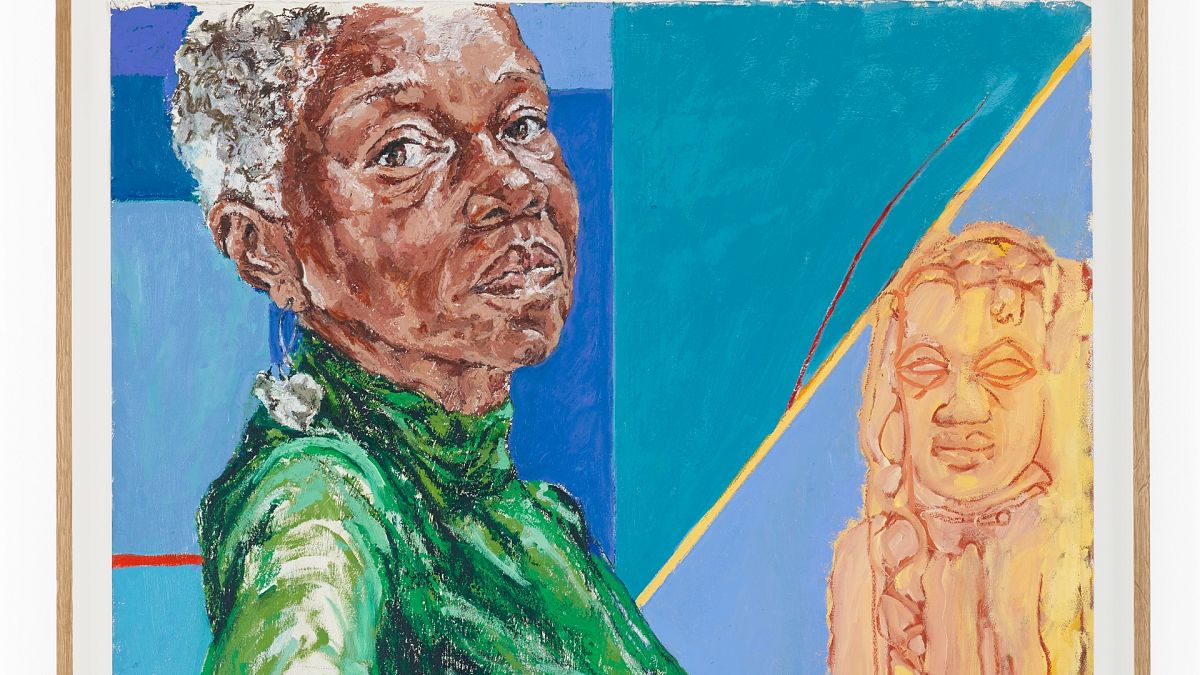

Finally, the last room is dedicated to Claudette Johnson, a longstanding member of the BLK Art Group. Her distinct portraiture work is on show here after she was nominated for two shows: ‘Presence’ at the Courtauld Gallery in London, and ‘Drawn Out’ at Ortuzar Projects in New York.

Johnson’s practice of passionately rendered portraits of Black women – and more recently men – makes her subjects larger than life and removed from specific backgrounds. The scale is a means of centring Black identity in Britain, and the abstract background as a way of signalling that “Black people have existed in the past, exist now, and will exist in the future, that we belong to all times”, she has said.

In person, these huge paintings communicate colossal depths of humanity. Each is so lovingly observed with playful abstract paintwork for clothing and form secondary to her vivacious faces. Johnson’s political point gives her work contemporary relevance, but the lasting impression of the entire exhibition is the beauty of her artistic skill in rendering the human form.