Using your body heat to power a watch or personal air conditioning system? It’s not as far-fetched as it sounds.

Body-heat powered devices are one step closer to reality after a design breakthrough.

You may not have considered your own body heat as renewable energy that could be harnessed. But given the exponential need for batteries in our electrifying world – and the pressure on planetary resources that brings – researchers have been testing this alternative for some time.

We all have the potential to be sustainable energy sources for wearable electronics, it turns out. There are just some teething issues with making the tech commercial.

One issue is making these wearable devices flexible enough. Now, researchers at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Australia have tackled this by developing a new, ultra-thin, flexible film that makes them comfortable and efficient.

How do wearable thermoelectric devices work?

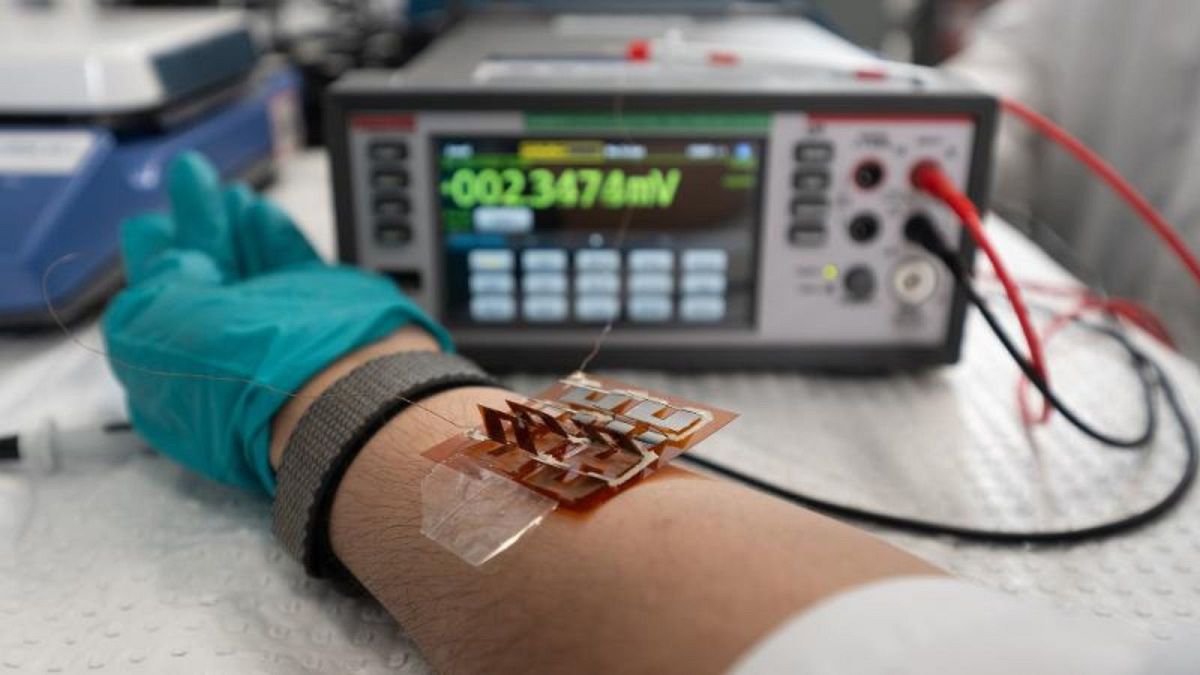

“Flexible thermoelectric devices can be worn comfortably on the skin where they effectively turn the temperature difference between the human body and surrounding air into electricity,” lead author of a new study on the breakthrough, Professor Wenyi Chen explains.

“However, challenges like limited flexibility, complex manufacturing, high costs and insufficient performance have hindered these devices from reaching commercial scale.”

Most thermoelectric prototypes are built with bismuth telluride: a semiconductor well suited to converting heat into electricity for low-power applications like heart rate, temperature or movement monitors.

The QUT-based team took things a step further by introducing tiny crystals known as ‘nanobinders’, which form a consistent layer of bismuth telluride sheets.

“We created a printable A4-sized film with record-high thermoelectric performance, exceptional flexibility, scalability and low cost, making it one of the best flexible thermoelectrics available,” says Professor Chen.

‘Solvothermal synthesis’ was used to do this: a technique that forms nanocrystals in a solvent under high temperature and pressure.

The film was then screen-printed, which allows for large-scale production, before being heated to near-melting point to bond the particles together.

From body heat to phone cooling

Chen and the QUT team foresee a wide range of possibilities for the tech.

As well as paving the way for wearable devices, like smartwatches, it could also be used to cool electronic chips – fitting inside tight spaces like smartphones and computers to help them run more efficiently.

“Other potential applications range from personal thermal management – where body heat could power a wearable heating, ventilating and air conditioning system,” adds Chen.