Roxana Mînzatu’s first working day as EU Commissioner saw member states fail to agree on new EU laws on internships – but she said abandoning laws intended to protect traineees’ workplace rights would be “out of the question”.

The EU’s newly employment commissioner Roxana Mînzatu on Monday vowed to press on with new rules to offer interns equal job rights – despite member states failing to agree on even a watered-down text.

Mînzatu’s first working day as Commissioner Vice-President for Social Rights and Skills saw her defending Brussels plans to improve the working conditions of over 3 million trainees, which she argued governments were trying to dismantle.

“We have concerns about the scope of the directive,” the Romanian Commissioner told reporters on Monday, after bemoaning new exemptions that would have cut its reach by 75%, by applying it only to “open market” posts that have no connection to education or training.

Mînzatu, who was a socialist MEP before taking up duties at the Commission, which formally started on Sunday, said she didn’t want to legislate for its own sake but would attempt to work with EU member states, who negotiate as part of the EU’s Council, to improve the law.

“I’m not talking of at this point, obviously, of withdrawing” the law, she said following the meeting of social affairs ministers in Brussels, adding: “It’s out of the question.”

On March 2024, Mînzatu’s predecessor Nicolas Schmit proposed the first-ever draft EU legislation to set legally binding minimum standards for trainees’ social protection, mentoring and pay – but it needs to be agreed by the Council and by the European Parliament to pass into law.

Mînzatu may have allies in the Council – such as Spain, which strongly opposed a draft law which it fears could lead to a race to the bottom, rather than offering young people new skills.

“Low cost is being prioritised over the need to promote education, and what it’s going to do is create an effect of substituting one worker for another,” Spanish Labour Minister Yolanda Díaz told her 26 counterparts.

While Baltic and Nordic EU countries appear on board with the latest draft, others such as Germany and Romania are hoping to continue discussions in the first half of next year, when Poland will take over from Hungary in chairing Council talks – though some claim that member states have already gone as far as they can in redrafting.

The current proposal, drafted by the Hungarian EU Council Presidency, is “the maximum that the majority of member states can agree with,” a senior diplomat told Euronews, adding that some countries wanted “a much more detailed and less flexible directive”.

The Commission’s initial proposal sets out principles that member states will have to apply to prevent jobs from being replaced or disguised as ‘traineeships’, including the ratio of staff to trainees, and the duration of contracts and interns’ tasks and responsibilities.

Mînzatu told social affairs ministers the text needs to keep strong anti-discrimination and enforcement measures, as trainees may find it hard to claim rights from a weak labour market position.

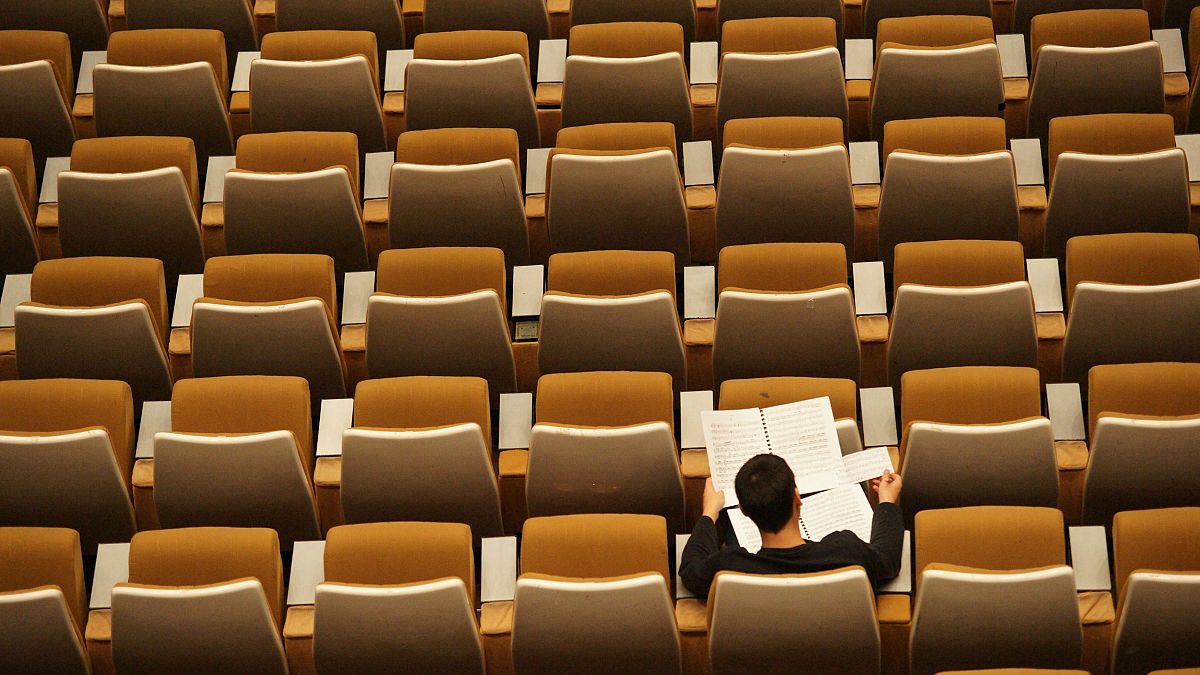

Unpaid internships cost more than €1,000 per month

Umbrella group the European Youth Forum and the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) welcomed the March proposal, but have now said the latest Council text fails to offer enough protection.

“We must address serious concerns about enforcement, especially as labour inspectorates are already underfunded and overstretched,” EYF president Rareș Voicu told Euronews.

ETUC confederal secretary Tea Jarc called on the Polish presidency to “convince member states to put national interests aside and work on a text that responds to calls from young workers across Europe to stop the exploitation of young people via unpaid and bogus internships”.

Unpaid internships cost a young person more than €1,000 a month, an EYF report found, underlining that they also hinder equal opportunities for Europe’s youth.

Youth organisations, trade unions and MEPs have long called for a ban on unpaid internships — but former EU Commissioner Schmit insisted this was outside the EU’s remit on employment issues.

“Working for free is a violation of international human rights law,” Voicu argued, adding that “now is the time to create a robust foundation that upholds their (young people’s) labour rights”.